It might mean that you never ask questions about the trauma – but that you recognise the signs, and open up opportunities for children to discuss their experiences without shame, or fear of being disbelieved.Ī sensitive place to start can be to get to know a child by talking about some of the other things in their life: their school mates, their brothers and sisters, the things they’re good at, their football team, what they do on a Saturday morning … not just their behaviours. Within a trauma-informed approach, curiosity isn’t about digging for answers or trying to get to the details of trauma, before the child is ready. Being curious asks you to step back from making quick assessments about a child – to keep an open mind, to watch, listen and wait. Taking a curious, trauma-informed approach can help practitioners understand a child’s daily experiences and the relationships that matter to them, and – eventually – can help a child talk about their concerns.Ĭuriosity – what you might call a ‘position of unknowing’ – is a real skill. Secrecy, fear and shame are common responses to trauma – powerful feelings that make it hard for practitioners to engage with children and start conversations that can lead to recovery. Sometimes this helps, sometimes it doesn’t (Kezelman & Stavropolous, 2019) … but the underlying trauma usually come to the surface, further down the track. Sometimes these children can be withdrawn – or acting out – and the focus shifts towards responding to these obvious behaviours. Children may fear for their safety, or the safety of loved ones. Often, a child won’t mention a traumatic event: it might still be a secret, or too raw, recent or risky for them to bring it up. Taking a trauma-informed approach – building your engagement around curiosity, safety, trust, and transparency – is a good place to start.

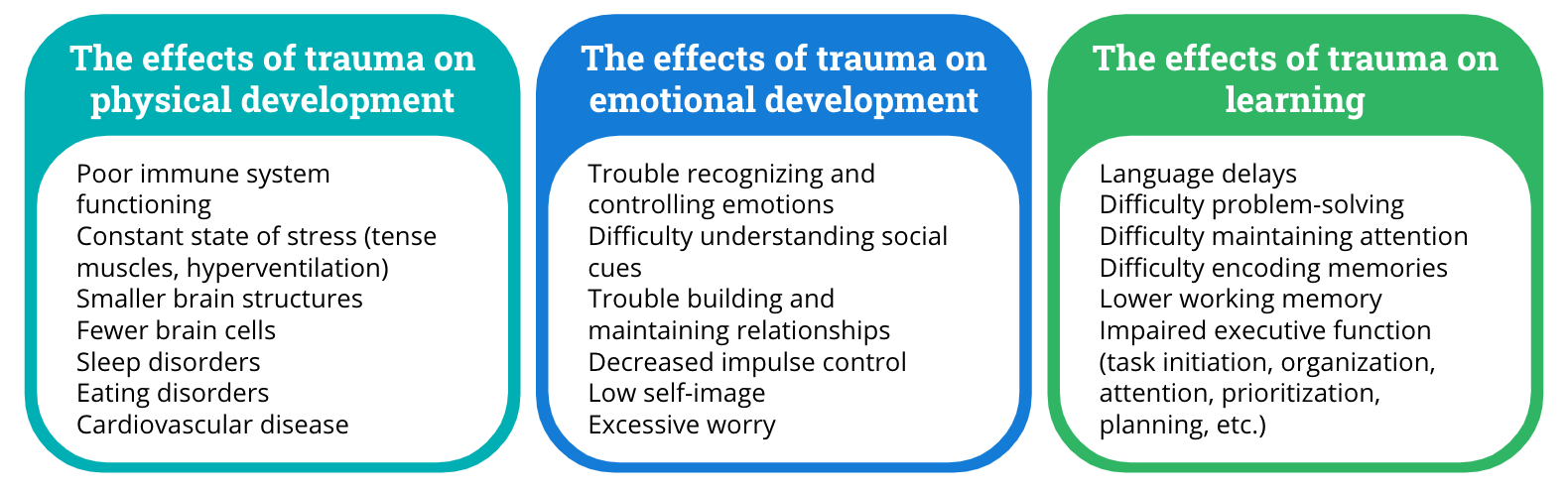

But with child psychologists’ waitlists ballooning out to three months and beyond, how can a practitioner help right now? And how can a practitioner, at any stage of the process, offer a child a sense of hope? So how does trauma effect children? And what can it mean for a child’s long-term mental health and wellbeing? Trauma has serious effects on the developing brain – impacts on comprehension, concentration and memory – and can lead to mental health difficulties, substance misuse, homelessness, unemployment … even things like increased rates of smoking, accidents and surgery (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2019 Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2014 Blue Knot Foundation, 2021). It’s clear that left unchecked, the impacts of childhood trauma can last a lifetime.įor a generalist practitioner – often the first point of contact – a quick referral may seem the easiest way to deal with an anxious, aggressive, or uncommunicative child (or their parents). Around 20% of Australian children are exposed to three or more adverse childhood experience (ACEs) (Olesen et al., 2010) – distressing situations they can’t control control (Burgermeister, 2007), like their parents’ financial or health problems, mental health struggles, marriage breakdown, or drug and alcohol issues. While many children grow up in safe and supportive environments, the insidious impacts of interpersonal trauma are still experienced by way too many. Statistics tell us that 57–75% of Australians will experience a traumatic event at some point in their lives (Mills et al., 2001 Rosenman, 2002).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)